There are fires that only get stoked when you try to put them out. Anna von Hausswolff is one of those: the censorship her concerts have faced in France under pressure from Catholic extremists has only served to double the attention paid to the talented Swedish musician. The daughter of experimental composer Carl Michael von Hausswolff, the singer-organist has been unclassifiable and fascinating since her debut album Singing from the Grave fifteen years ago, blending gloomy gothic atmospheres, jazz and soul influences, and electronic sounds with impressive lyrical power. We particularly loved her darkest work, the 2018 album Dead Magic, and have been longing for a new studio album since the 2020 instrumental All Thoughts Fly.

We are therefore delighted that her sixth studio album is being released this year. There is also a singular power in the fact that it is entitled Iconoclasts: what has Anna von Hausswolff done with her career if not break down existing frameworks, preventing us from sinking into idolatry? She herself explains in an interview that the central theme of the album is questioning and the liberation it leads to, which allows us to find something new by freeing ourselves from an illusion, a system, or a relationship.

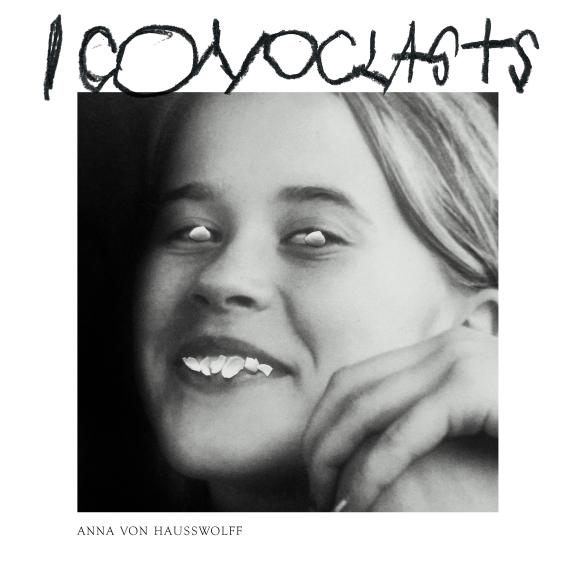

As the cover illustration suggests, don't count on Anna von Hausswolff to remain confined to the image we have of her. At the risk of rubbing us up the wrong way, Iconoclasts is a resolutely luminous album, which develops its melodies smoothly and whose sounds remain soft. You could say it's a pop album, in its own way. And yet Iconoclasts is everything that pop music generally isn't: deep, powerful, and above all personal and authentic.

Because even if the album doesn't strike us, it carries us away, taking us to heights we never imagined we could reach: most of its melodies are constructed like cascading crescendos, which sweep us away all the more because the instrumentation is so incredibly rich; aside from her pipe organ, synthesizer, and the usual rock instruments, which is already a lot, Anna von Hausswolff has brought in several violins, a saxophone, a clarinet, a viola, and even a cello! Yet Iconoclasts never feels chaotic: on the contrary, it is brilliantly articulated, with the strings and organ giving the music a deep gravitas, while the drums bring rock energy and Otis Sandsjö's saxophone twists and turns in sinuous melodies in the foreground. And then there's the vocals, which make a sensational comeback after the previous album! It is a great pleasure to hear Anna von Hausswolff's voice again, not so much for its high pitch as for the power she puts into it. Paradoxically, while her music has never been so clear, Anna's singing often ends in a scream, bringing her songs to a heart-wrenching climax. But she doesn't do it alone: Iconoclasts features the voices of three guests, Iggy Pop, whose deep timbre contrasts with that of the Swedish singer, American singer Ethel Cain, and Anna's sister, Maria von Hausswolff, who usually works as a director of photography.

You don't perceive the full richness and power of this ensemble on first listen, but you immediately realize that it carries something strong, something that grabs you more and more with each listen. What overwhelms us in these pieces is a feeling of joyful liberation, because most of them are constructed in such a way that the crescendo gives us the impression of escaping from the adversity of more static, disturbing, or melancholic elements; it is escaping from what weighed us down by being iconoclastic that gives us this feeling of power.

While the theme is strongly asserted, the tracks themselves display a wide variety of structures and sounds. With so many tracks, it's no surprise that there are some uneven moments, and indeed there are: The Whole Woman, on which Anna sings a duet with Iggy Pop, is ultimately one of the least memorable due to its somewhat overly smooth melody, but even this track has its own particular charm thanks to the sombre atmosphere created by its harmony, as does the long, ethereal suspension of An Ocean of Time, featuring the mysterious keyboardist Abul Mogard. On the other hand, there are masterpieces in this ocean, the tracks where the struggle is most bitter: this is the case with The Iconoclast, where Anna von Hausswolff's vocals abandon all restraint to cry out her desire to change things, and even more so with Struggle With the Beast, a quasi-instrumental piece where the saxophone battles at length before the singer comes in to expose the fear she must face, the most epic track on the album. Others captivate us just as much in different ways: we thrill to the tension slowly distilled by The Mouth, with lyrics full of fragility behind which lies a wild force, we experience the cathartic breakup of Stardust, and we even sigh along with the melancholic ballad Aging Young Women, where Anna von Hausswolff and Ethel Cain join voices to sing about the fear instilled in women that they will miss out on life if they don't have children as they get older. And then there is that final poignant moment at the end of Unconditional Love, where the two von Hausswolff sisters abandon themselves to a memorable chorus. From the intro The Beast to the conclusion Rising Legends, an hour and thirteen minutes have passed without ever feeling long, so strong and varied is Iconoclasts.